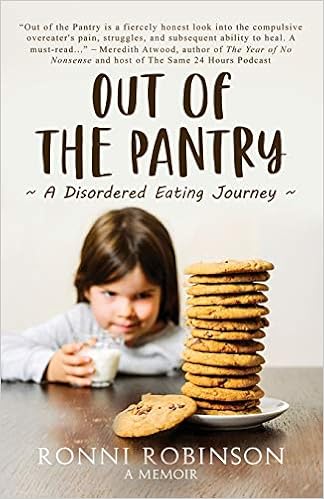

An Excerpt from “Out Of The Pantry: A Disordered Eating Journey”

In her first memoir, Ronni Robinson shares her story of growing up and developing a binge-eating disorder. In secret and shame, she overeats and binges through tween years, high school, college, an abusive first marriage, and even a loving second marriage. A brutally honest glimpse into the trials, pervasive thoughts, and heartbreak of a compulsive overeater, discover how Ronni gains the courage and strength to live her life without being a slave to food.

I was working at the cotton candy machine at my children’s school carnival. Alyssa, a fourth grader, was hanging out with me and another mom when she said she was hungry, so I took her to the pizza stand and bought her one slice and a bottle of water.

Though I knew I would have my own slice a little later as part of the food plan I’d developed for the day, I couldn’t stop thinking about how much I wanted to eat the crust of her pizza, which I knew she didn’t like. I rationalized that it would only be one additional pizza crust that was outside my food plan, and I also knew I would be accountable for it, dutifully recording it in my daily food log that evening.

A large slice of pizza on a flimsy paper plate can be challenging for a nine-year-old to balance on her lap. It didn’t take long for the pizza to slip off the plate and down to the ground. Even though it landed crust-down, and I’m a five-second-rule mom in the house, we both knew the pizza was trash.

As we approached the pizza stand for another slice, I explained to Alyssa that she needed to hold the plate tighter so the pizza didn’t slide off again. I was still thinking about that crust and reminded her, somewhat urgently, that Mommy wants to have it. I served some people cotton candy, and the next thing I knew, I saw my daughter walking back the fifteen steps from the large trash can in the middle of the food area after throwing out her plate.

She threw the crust away.

The crust that I had asked her for more than once. I could feel my heart beating faster. Desire ran through me from head to toe. My only goal, my only focus, was eating that crust.

“Alyssa! I told you to save that crust for Mommy!” I scolded, an uncharacteristic harshness in my voice.

“Sorry, Mommy, I forgot.” She looked down to the ground, but then her head popped up when she saw a friend, and she skipped off.

Don’t you know how important that crust was to me?

Without thinking, I strode to the trash can and confirmed that my daughter’s paper plate, with her napkin placed neatly over the remaining bites, was sitting right there on top of the rubbish. I grabbed it and started biting off chunks of crust while returning to the cotton candy station. Though the crust was burnt, and less doughy than I liked, my mind had been made up to eat that crust. There was no turning back.

Suddenly, my brain clicked. I realized that at a school event, in front of many parents, teachers, and children I knew, I had retrieved food out of a public trash can and was eating it in plain view. And I had practically yelled at my daughter for throwing it away.

Shame coursed through me.

We lived in a small upper-class suburb northeast of Philadelphia where everyone knew practically everyone. I fought the urge to poll my parent friends and acquaintances about whether they’d seen what I’d done and then make up some sort of excuse to explain myself. What could I possibly say? Are they all whispering behind my back? Shit!

Shit!

I was definitely not as recovered as I’d believed. With all that I was learning in therapy, at Overeaters Anonymous (OA) meetings, and from the books I was reading, I’d thought that I was done with this kind of behavior. But an eating disorder is insidious—especially one like mine, which had taken root firmly during adolescence and flourished well into adulthood. Clearly, I still had a lot of work to do.

Instead of hiding, however, I immediately sought out my husband, who was walking around the carnival with our seven-year-old son, Devon. I pulled Efrem close so I could whisper in his ear. “I just ate Alyssa’s pizza crust out of the trash can,” I explained, adding, “What is wrong with me?”

As calm as always, he hugged me close. “It’s okay, Ronni. I’m sure no one saw you. Try not to worry about it.”

“Thanks,” I said. Easier said than done.

Next, I sought out a friend at the carnival who had confided that she had a similar eating disorder and who also attended OA meetings. Ever the practical person, she told me, “It’s done. Put it behind you and move on.”

I knew she was right, but it wasn’t until the next day that I could begin to understand what had happened and why. And to realize that I was still letting a mere object—food—control my thoughts and my life.

But it’s hard to break patterns—of thinking, of eating—that go back more than thirty years.

You can buy Out Of The Pantry on Amazon or at Barnes & Noble.